ROME’S FORMING FAMILIES

I. INTRO

Throughout history, from the 15th century to the 18th century, powerful families have shaped the city of Rome. How have these families altered and preserved the form of the city? While various prominent families have been a driving force throughout the history of Rome, for the purpose of this paper they have been divided into two groups: baronial families of Medieval times and Papal families. By comparing these two types with different levels of power and limitations, we can more accurately understand the scope and lasting effect of their efforts. The Margani Family will serve as a guide in the exploration of the effects that medieval families had on the urban fabric of Rome. Their accomplishments and contemporary presence in the city will be compared with the urban upheaval carried out by the Barberini Family.

II. PIAZZA MARGANA

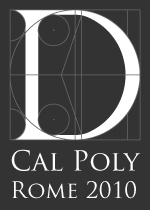

Figure 1 Figure 2

Piazza Margana is a small area at the base of the Capitoline Hill, the historical civic center of Rome and a current transportation and tourist hub. It exists as another world separate from the chaos of Rome. This little section of the Sant’ Angelo Rione stands out as a distinct cluster, still recognizable from the Nolli Map. Why is this section different from the others around it? How did a medieval development remain intact in an area that has gone through several transformations over the centuries? Why was it not sacrificed in the development of the civic center of Rome, when even churches were not spared?

i. The Role of Medieval Families in Shaping Rome

Fourteenth century barons transformed Rome by raising towers and building fortified residences. During these tough times with the absence of the Pope, fortresses were necessary to ensure security. “Medieval barons like the Cenci, Santacorce, Orsini and Colonna had their way unopposed,” creating an environment of violence and rivalries.[i]

The return to order of the Papacy in 1417, marked the next stage in the medieval families’ influence on the urban fabric. This was a time of conflict between the papacy and the families of Rome. With the presence of the pope the barons were “deprived of the ability to express their domination through overt displays of violence” and they resorted to the use of architecture to show authority.[ii] One example of this was at the Santacorce fortress, which was rebuilt in 1501, “the ground floor façade [was faced in] ‘diamond-point’ stone work.”[iii]

The common characteristics of the “fortification” of a family’s power can be described as a complex set above its surroundings, the presence of a family church, self-advertisement, and branches of the family living close to each other.[iv]

These could generally be found within the three main forms of baronial estate classified by Majanlahti: the monte acting as a landmark for a family, the contrada or neighborhood dominated by a family, and the isola, which creates a sense of unity within a smaller area.[v] The tower, not without its strategic value, was “the ultimate status symbol” that completed many of the noble residences in the fifteenth century.[vi]

ii. Piazza Margana: Historical Overview

When walking around Rome, it appears that over time, most other Medieval fortifications have disappeared following the extinction of the family or have been altered beyond recognition. They no longer standout and are incorporated into the buildings that went up around them. The Margani neighborhood is an exception to this observation. However, like most other medieval fortifications in the city of Rome it was likely that the Margani family lived close to each other for protection as well as prestige, “reinforcing the pervasive sense of social hierarchy.”[vii]

iii. Piazza Margana: Analysis of a Medieval Enclave

The turning point mentioned earlier began as a result of the 1480 murder of Pietro Margani by Prospero Santacorce at the gate of the Tor Margana. In response Sixtus IV della Rovere demolished the Santacorce Fortress, expressing his dominance over the baronial families.[viii] A more exaggerated expression of dominance through architecture occurred after this date. “The builders achieved visual authority in two ways: first, by constructing a tower on the corner; second by decorating the ground-floor facade.”[ix] Since the Margani complex has remained relatively intact since before this point, the buildings appear clear of such embellishment. They expressed dominance in more traditional ways, with the creation of an enclave.

Isola

The Margani fortress forms an isola, with Piazza Margana as the entrance. The series of connected buildings which is completed by the Tor de’ Specchi, creates a sense of unity.[x] Their medieval fortification can be seen as a city unto itself. George Gorse observed that, “in the city, Genoa’s noble families created strongholds reminiscent of their fortified, towered houses in the countryside.”[xi]

This can be seen in Rome, and more specifically in the Margana enclave. They created a fortified city within a city, based on the idea that, the ideal fortress cities were “conceived as a whole and divided into functionally different parts.”[xii]

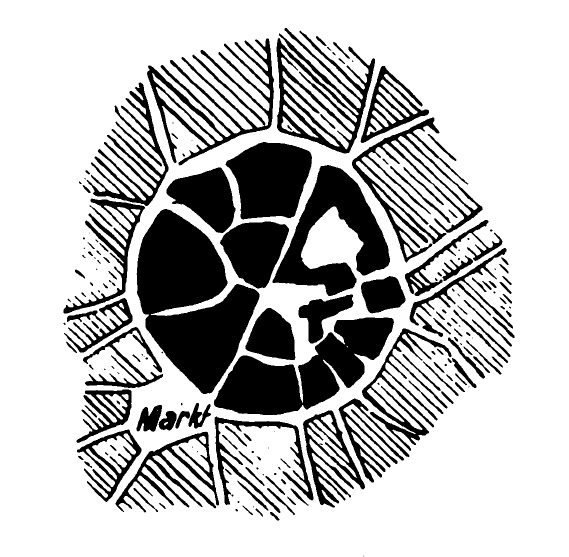

Radio-centric

The characteristics of the edge of an isola fortification would have been decided by what created the most security. As Blumenfeld discusses, this would be “the shortest line enclosing a given area…the logical form where security is paramount and natural boundaries are lacking.”[xiii] Circulation was also a key factor in the development the isola’s form. In the case of the Margana Fortress, “the combination of a city wall and converging streets creates the radio-centric plan.”[xiv] Such an urban form is “developed from the outside in, the outer contour is clearly defined, while the interior street pattern is indefinite.”[xv] Large and rather monolithic facades make up the outside edge of the Margana neighborhood. The outsider encounters an overwhelming “welcome.” While the roads take bending routes, they lead to the center and eventually out to the other side. This would have served as a security measure in the past. Today, it contributes the slower pace that one experiences within the Margana neighborhood.

Still Works Today

The radio –centric plan remains in place today “thanks to [its] inherent simple logic, the old forms could serve new functions.”[xvi] The Margani created a very cohesive group, separate from everything around it. However, the enclave is still able to connect with the surroundings using its already existing road system. The Margana neighborhood remains separated yet incorporated into a modern city. The enclave, in the context of the modern city has the benefits of creating a quiet, comfortably scaled district in the heart of the city and appears to be successful in housing residential spaces as well as small businesses. This simultaneous preservation and integration is not as easily accomplished with contrada or monte fortifications. The isola is a much more cohesive form. By enclosing itself with the least amount of surface area facing the outside world and isola is protected for interventions. The contrada is easily lost over time, invaded by newer consecution. Perhaps, because it was not originally conceived as a whole, it can’t withstand the changes that come with time. The monte’s dependence on landscape limits its ability to adapt over time, while maintaining its overall form.

Another World

Walking through Piazza Margana and the streets that branch off from it, there is an immediate change. Gorse states that, “architecture and piazza worked together to create an open, light-filled, tranquil urban place – a still ‘eye’ in the center of the medieval urban hurricane.”[xvii] Today, in Piazza Margana this feeling still registers. It is no longer a safe haven from rival baronial families but now serves as a relief from the chaos of tourism. It appears (in comparison to other groups) that the Margani were the most successful at creating its own fortified world where the Piazza Margana and its surrounding lanes are a microcosm of Roman life.

Walking into this neighborhood with no prior knowledge the thought arises that this area would be ideal refuge for a modern day mafia. Feeling like an outsider and venturing into a defensive world, there is a sense of mystery about what occurs behind the walls and of a collaborative community. Upon research it all becomes clear, this aura is still present from the original intent.

iv. Social Context

“By the middle of the sixteenth century…changing attitudes toward specific social categories led to policies that had an impact on the urban fabric. The active homogenization of urban society… culminated in the establishment of the Jewish Ghetto in 1551.”[xviii] This marked the beginning of “dismantling of baronial enclaves, in a city now subject to centralized administration, reconfigured the urban fabric. Clans of ancient origin remained anchored to the quarters in which they had held sway, but patrician families of more recent formation elected more socially uniform palatial districts as their residences.”[xix]

v. History and Development of the Surrounding Area

Several buildings just outside of Piazza Margana were torn down in 1928 in preparation for the Vittorio Emanuele II Monument. Again in 1939, Piazza Margana and the medieval buildings narrowly escaped being destroyed when Via del Mare, now Via del Teatro di Marcello was enlarged. Next to Piazza Margana, Palazzo Massimo was not as lucky; its corner was cut. Via del Mare was created to liberate the ancient monuments in the area and eventually was connected to the sea. Mussolini cleared the residential neighborhood to glorify the monuments of Rome, which now stand out in the open. “No visitor to Rome in the 1930s could fail to see this new fascist street in the heart of historic Rome. It remains today as a major example of the fascist urban landscape, unchanged except for the name.”[xx] Its role today as a buffered precinct, protects the enclosed neighborhood from the chaos of tourism. The new roads and traffic tend to isolate and protect the area even more. The location of the Teatro di Marcello, the Portico di Ottavia, the Roman Forum, and the Camplidoglio meant that Via del Teatro di Marcello had a very limited path it could take. In part, Piazza Margana was preserved because of its location in the midst of such sensitive pieces of history.

III. PIAZZA BARBERINI

Figure 4 Figure 5

Rulers often play key roles in shaping a city, from Mussolini to Sixtus V, they have left their mark. However grand the changes of rulers have been, there is something subtle and pervasive in the way families shape the city. They place the roots from which the city grows. Perhaps a better understanding of this could be gained from studying the duality of family and leader, using the example of the Barberini Family.

i. The Barberini Family and Their Role in the Development of Rome

Unlike the Margani Family the Barberini had the power, money, and at times the Papacy itself to influence the urban fabric. While the Barberini Family had widespread influence, focusing on Piazza Barberini allows for comparison with the Margani Family. The Barberini as one of “the great families of the seventeenth century… focused their attention on splendor rather than sovereignty: instead of conquering and ruling their own territory, their ambitions lay in Rome itself.”[xxi]

While the Barberini Family started from a more humble background, they were able to reach the top of Rome’s society through continuous involvement in the Church and strategic marriages. At the height of the family’s success they were able to leave a lasting impression on the urban fabric of Rome. As Carla Kayvanian asserts, “Their intervention exemplifies the dramatically increased scope of the urban projects that patrician families implemented in the seventeenth century, and the role they played in the formation of the early modern city.”[xxii]

ii. Barberini Pope – Historical Overview

The rise of the Barberini Family began when Maffeo Barberini was elected Pope in 1623 as Pope Urban VIII. Pope Urban VIII was responsible for a transformation of the city, “the Baroque winged into Rome on the backs of the Barberini bees.”[xxiii] Pope Urban VIII was a patron to many remarkable artists, including Bernini who’s creativity transformed the city. Pope Urban VIII was interested in the advancement of the Catholic Religion through architecture and he focused on building churches, a number of which were located on the Quirinal Hill around his family palazzo.[xxiv] It was because of Urban VIII that the Barberini were able to carry out many of their urban alterations with the support and help of the Papacy.

iii. Urban Fabric Analysis of Piazza Barberini Area

The Barberini have had a lasting effect on the architecture of Rome, especially in terms of marking the beginning of a style. According to Anthony Blunt, Palazzo Barberini “was the first great Baroque palace to be constructed in Rome.”[xxv] Palazzo Barberini took over a large and very prominent area of the Quirinal Hill

The area around Piazza Barberini was still somewhat rural when Cardinal Francesco Barberini purchased the former Palazzo Sforza in 1625. He soon transferred the title to Taddeo and with the help of their uncle Urban VIII construction was completed in 1633. “The palace was meant as a showpiece…but it also had to house two different aspects of the family: the secular side…and ecclesiastical side.”[xxvi] Carlo Maderno decided on an “H” shaped plan, which incorporated the old Palazzo Sforza, to separate the two groups. After Maderno’s death in 1629, Bernini and Borromini took over.

“Bernini… had hardly touched the field of architecture… [it] is, therefore, intrinsically probably that Bernini would have followed the plans of his predecessor to a great extent.”[xxvii] It appears that this prudent approach, worked in Bernini’s favor. The piazza, renamed for the Barberini Family, houses the Fontana di Tritone, one of Bernini’s first commissions from Urban VIII in 1642. This area also served as an important ceremonial and grand entrance to the palace.

Rather than closing themselves in, the Barberini Family reached out to gain influence in the area surrounding their palazzo. The Barberini occupied a large area centered on the piazza. When Urban VIII became Pope, his brother, Cardinal Antonio the Elder joined the Franciscan order now associated with Santa Maria Della Concezione. Urban VIII was responsible for helping them building their church and monastery on a piece of land next to the family palace.

“Nearly all of its chapels [were] simultaneously sponsored by different members of the Barberini Family, making it, more than any other church, an expression of the artistic and spiritual interests of the family.”[xxviii] This is an example of Urban VIII’s undisputed power as well as the rest of the family’s invested involvement in the efforts. Cardinal Francesco Barberini sponsored the construction of the nearby San Carlo di Quattro Fontane. Their interest in the development of the area shows how the freedom of money allowed the Barberini Family to reach far across the city.

iv. History and Development of the Surrounding Area

The construction of via del Tritonte in 1911-25 transformed the quite piazza into a center of transportation. This, along with the demolition of Cardinal Antonio’s theatre and the reduction of the cortile della Cavallerizza by Mussolini has changed the area significantly. The Palazzo no longer dominates the piazza, as new buildings have blocked the old formal entrance to the palace. The monastery of Santa Maria Della Concezione was destroyed when via Veneto was cut in 1886-9. In the case of the Barberini neighborhood, new streets and piazzas altered the family’s contributions. The Barberini transformation, as an extension of their power, was more easily upset.

IV. COMPARISON

The Barberini’s development of Rome through extension and display of power, contrasts with the Margani efforts of protection and consolidation. While the medieval families of Rome had an impact on the form of the city, they were held back by financial and political constraints. This can be seen as a contrast to the almost unlimited power and financial freedom that sixteenth and seventeenth century families enjoyed, especially during the reign of the their family pope.

Papal families, beginning with the Barberini, tended to make more grand moves that spread over a larger area. Their connection to Papal power and their financial strength fostered transformation and development that had a higher probability of future response and change. Without the Papacy they could no longer maintain their hold. By working at scale of the whole city, later rulers were more likely to interfere with and adjust what they had already put in place.

Piazza Margana is part of very solid and tight block, contributing to its resistance to change and allowing it to remain untouched by urban interventions. The medieval families based their compounds on security and fortification. Self-preservation gave them protection from other baronial families. This legacy, although unintended, helped to protect their enclave from future urban upheavals.

Figure 1 Piazza Margana – Nolli Map image, Nolli Number 994

Figure 2 Piazza Margana – Google Earth image, accessed November 30, 2010

[i]Majanlahti, Anthony. The Families Who Made Rome: A History and Guide. London: Pimlico, 2006. p.5

[ii] Majanlahti, Anthony. The Families Who Made Rome: A History and Guide. London: Pimlico, 2006. p19

[iii] Majanlahti, Anthony. The Families Who Made Rome: A History and Guide. London: Pimlico, 2006. P.17

[iv] Gorse, George. “A Family Enclave in Medieval Geona.” Journal of Architectural Education Vol. 41, No. 3 (Spring, 1988): 20-24. Accessed November 18, 2010. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1424889.p 21

[v] See Majanlahti, Anthony. The Families Who Made Rome: A History and Guide. London: Pimlico, 2006. P. 9-28 for more information on medieval fortification forms.

[vi] Majanlahti, Anthony. The Families Who Made Rome: A History and Guide. London: Pimlico, 2006. p.17

[vii] Gorse, George. “A Family Enclave in Medieval Geona.” Journal of Architectural Education Vol. 41, No. 3 (Spring, 1988): 20-24. Accessed November 18, 2010. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1424889. p24

[viii] Majanlahti, Anthony. The Families Who Made Rome: A History and Guide. London: Pimlico, 2006. p. 17 discusses in detail the feud between the families that were from rival clans.

[ix] Majanlahti, Anthony. The Families Who Made Rome: A History and Guide. London: Pimlico, 2006. p.17

[x] Tor de’ Specchi is a monastery supporting a congregation formed in 1433 by S. Francesca Romana http://www.tordespecchi.it/public/en/index.php?Who%26nbsp;_we%26nbsp;_are

[xi] Gorse, George. “A Family Enclave in Medieval Geona.” Journal of Architectural Education Vol. 41, No. 3 (Spring, 1988): 20-24. Accessed November 18, 2010. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1424889. P. 21

[xii] Blumenfeld, Hans. “Theory of City Form, Past and Present.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians Vol. 8, No. 3/4 (Jul. – Dec., 1949): 7-16. Accessed November 18, 2010. http://www.jstor.org/stable/987432. p7

[xiii] Blumenfeld, Hans. “Theory of City Form, Past and Present.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians Vol. 8, No. 3/4 (Jul. – Dec., 1949): 7-16. Accessed November 18, 2010. http://www.jstor.org/stable/987432. P.9

[xiv] Blumenfeld, Hans. “Theory of City Form, Past and Present.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians Vol. 8, No. 3/4 (Jul. – Dec., 1949): 7-16. Accessed November 18, 2010. http://www.jstor.org/stable/987432. p.9

[xv] Blumenfeld, Hans. “Theory of City Form, Past and Present.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians Vol. 8, No. 3/4 (Jul. – Dec., 1949): 7-16. Accessed November 18, 2010. http://www.jstor.org/stable/987432. P.11 explains the formation of radio-centric cities and the contrasting gridiron form.

Figure 3 Radio-centric city plan

Blumenfeld, Hans. “Theory of City Form, Past and Present.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians Vol. 8, No. 3/4 (Jul. – Dec., 1949): 7-16. Accessed November 18, 2010. http://www.jstor.org/stable/987432. p.10

[xvi] Blumenfeld, Hans. “Theory of City Form, Past and Present.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians Vol. 8, No. 3/4 (Jul. – Dec., 1949): 7-16. Accessed November 18, 2010. http://www.jstor.org/stable/987432. P.10

[xvii] Gorse, George. “A Family Enclave in Medieval Geona.” Journal of Architectural Education Vol. 41, No. 3 (Spring, 1988): 20-24. Accessed November 18, 2010. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1424889. P. 22

[xviii] Keyvanian, Carla. “Concerted Efforts: The Quarter of the Barberini Casa Grande in Seventeenth-Century Rome.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians Vol. 64, No. 3 (Sep., 2005): 292-311. Accessed November 18, 2010. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25068166. p.292

[xix] Keyvanian, Carla. “Concerted Efforts: The Quarter of the Barberini Casa Grande in Seventeenth-Century Rome.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians Vol. 64, No. 3 (Sep., 2005): 292-311. Accessed November 18, 2010. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25068166. p.292

[xx] Painter, Borden W. Mussolini’s Rome :Rebuilding the Eternal City. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005. P.12

Figure 4 Piazza Barberini – Nolli Map image, Nolli Number 214

Figure 5 Piazza Barberini – Google Earth image, accessed November 20, 2010

[xxi] Majanlahti, Anthony. The Families Who Made Rome: A History and Guide. London: Pimlico, 2006. p.5

[xxii] Keyvanian, Carla. “Concerted Efforts: The Quarter of the Barberini Casa Grande in Seventeenth-Century Rome.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians Vol. 64, No. 3 (Sep., 2005): 292-311. Accessed November 18, 2010. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25068166. P. 293

[xxiii] Majanlahti, Anthony. The Families Who Made Rome: A History and Guide. London: Pimlico, 2006. P.219

[xxiv] See Majanlahti, Anthony. The Families Who Made Rome: A History and Guide. London: Pimlico, 2006, for more examples of the role Pope Urban VIII played in the architecture of churches.

[xxv] Blunt, Anthony. “The Palazzo Barberini: The Contributions of Maderno, Bernini and Pierto da Cortona.” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes Vol. 21, No. 3/4 (Jul. – Dec., 1958): 256-287. Accessed November 18, 2010. http://www.jstor.org/stable/750826. P.256

[xxvi] Majanlahti, Anthony. The Families Who Made Rome: A History and Guide. London: Pimlico, 2006. p.239

[xxvii] Blunt, Anthony. “The Palazzo Barberini: The Contributions of Maderno, Bernini and Pierto da Cortona.” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes Vol. 21, No. 3/4 (Jul. – Dec., 1958): 256-287. Accessed November 18, 2010. http://www.jstor.org/stable/750826. P.263

[xxviii] Majanlahti, Anthony. The Families Who Made Rome: A History and Guide. London: Pimlico, 2006. p.256