Rediscovering the Role of the Architect as Poet: Understanding Metaphor in the Work of Bernini

Alex VincentNo matter how much humans strive for absolute truth, the change of meaning through time continues to keep it out of grasp. What is meaningful in one time or in one culture may be meaningless in another. In the case of Gian Lorenzo Bernini and Baroque Rome, there is much we can learn if we approach the time with an understanding of how seventeenth-century Romans found meaning. Looking back into history then, perhaps a common thread can be found that brings lessons from the past through time to become applicable today. This paper attempts to use poetics and narrative in architecture as a way of looking at Bernini’s work, in this case the Baldacchino, to see what can be applied in a contemporary design approach.

After the height of the Renaissance had passed and the Council of Trent had created new reformations for the Catholic Church, Roman art and architecture changed drastically. With the geocentric worldview shattered and the structured harmony of cosmos gone, the quest for ‘universal man’ was replaced with a new search for stability.[i] In the Baroque age, the metaphysical structure began emphasizing persuasion and participation, which as described by Norberg-Schulz,

…may be characterized as a great theater where everyone was assigned a particulate role. Art, therefore, was of central importance…Its images were a means of communication more direct than logical demonstration, and furthermore, accessible to the illiterate. The art of the Baroque, therefore, concentrates on vivid images of situations, real and surreal, rather than on “history” and absolute form.[ii]

In Rome especially, the reformed church was looked to as a source of this imagery, creating a rich artistic language that “became official and…institutionalized…” and artist like Bernini were commissioned heavily by the ruling papacy.[iii] As Baroque Rome began to fulfill the decrees of the counter-reformation doctrines and the artistic imperatives of the early seventeenth-century popes, Roman churches began to fill with elaborate painting and sculpture, bringing the stories of the bible to life. Though these images became literal visual representations of the biblical text, they did not attempt to rationalize the stories, but rather embellish their fantastic qualities. Theatricality in these dramatic images enriched the stories and brought new metaphor and meaning to well known readings. Such an emphasis on elaborate imagery brought forth an age of poetics– not just in literature, but also in art and architecture.

One of the best-known poet-architects of the Roman Baroque was Gian Lorenzo Bernini. The son of a Florentine sculptor, Bernini inherited both a talent for art and devoutness to the Church. His passion for sculpting and the church became quickly noticed by Pope Urban VIII. A poet in his own right, the Pope compelled Bernini to pursue the rich imagery and sense of mystery brought about by the counter-reformation. Unlike the search for clarity in the Renaissance, Philipp Fehl proposes baroque imagery became a ‘hermetic science’, a practice “concerned with the protection of mysteries, with showing the truth in layers…”[iv] Religious art and architecture became poetic and truth expressed through allegory. In this way, the tradition of religious mystery, initiation, and ritual is preserved and enhanced. Fehl expresses the playfulness and potential of poetical imagery well:

The truth of art, on the other hand, of all the poetic arts, rises on the wings of fiction, a sweet pretense that in the language of play and well-agreed-upon illusion appears to us in an image, unreachable to the touch and yet visible to all. It elevates a story from the particular circumstances, which narrowly define its validity to the light of timelessness. Being all play, its truth dances on top of the scaffolding that holds up the story or the mystery, which it serves. It is a part of what it tells and yet it transcends it, or better, transforms and advocates it in such a fashion that it offends no one but pedants, and consoles, delights, and instructs all men.[v]

As an architect, Bernini continued to emphasize sculpture as the primary means of creating allegory; with space becoming a backdrop expressing “Baroque ‘mystery in action’ by the plastic decoration…”[vi] Yet Bernini went beyond merely haphazardly covering an interior with ornamentation. Bernini used concetti – artistic goals and poetic meanings that he wished to convey in a piece – to guide his works and define “the essential meaning of his subject; it was never, as so often in seventeenth-century art, a cleverly contrived embroidery.”[vii] One of his repeated concetti seen throughout his sculpture and his architecture was his vision to capture the moment of climax in the narrative being told, right where tension is greatest and the subject most expressive. To bring this action to his architecture, Bernini began blending the lines between architecture and sculpture.

This innovation is seen perhaps seen most clearly in the Baldacchino over the tomb of St. Peter. The elegant canopy standing proud at the center of the Catholic Church seems to possess the same dynamic energy of Bernini’s sculpture. The columns themselves take on a sculptural liveliness as they spiral upwards (Fig 1). Their shifting form becomes many things: a reference to the similarly shaped columns of the old St. Peters, a contrast to the massive vertical supports of the dome behind, and a structural innovation that did not require the typical superstructure to erect the columns.[viii] The black bronze further separates the Baldacchino from white marble around while bringing out the gold leaf splendor of its emblems and biblical characters. In the heavy air of St. Peters, the dark bronze seems almost to disappear, leaving the golden images floating in space, smiling down to visitors, so alive and expressive that Bernini welcomes our imagination to bring the canopy to life. Bernini used intricate details to complete his narrative: the hanging cloth drapery seems to blow in the wind, lizards scamper up the base of the columns, even medals and rosary sit just in reach as if placed by past pilgrims – all vividly cast in the bronze (Fig 2).[xi] Such moments activate the visitor’s imagination, transporting them to “the open air of a heavenly Jerusalem as it were, where lizards crawl and flies buzz, all in a life of gold.”[x] The spatial narrative that is created by the Baldacchino’s imagery connects Rome to Jerusalem and thus the meaning as holy canopy to Bernini’s baldachin. Though the references were conceived from sculpture, meaning was derived from the architecture, which facilitates a spatial dimension to the work – one that causes the meaning to be revealed through the active experience of space rather than through a passive symbology.

This innovation is seen perhaps seen most clearly in the Baldacchino over the tomb of St. Peter. The elegant canopy standing proud at the center of the Catholic Church seems to possess the same dynamic energy of Bernini’s sculpture. The columns themselves take on a sculptural liveliness as they spiral upwards (Fig 1). Their shifting form becomes many things: a reference to the similarly shaped columns of the old St. Peters, a contrast to the massive vertical supports of the dome behind, and a structural innovation that did not require the typical superstructure to erect the columns.[viii] The black bronze further separates the Baldacchino from white marble around while bringing out the gold leaf splendor of its emblems and biblical characters. In the heavy air of St. Peters, the dark bronze seems almost to disappear, leaving the golden images floating in space, smiling down to visitors, so alive and expressive that Bernini welcomes our imagination to bring the canopy to life. Bernini used intricate details to complete his narrative: the hanging cloth drapery seems to blow in the wind, lizards scamper up the base of the columns, even medals and rosary sit just in reach as if placed by past pilgrims – all vividly cast in the bronze (Fig 2).[xi] Such moments activate the visitor’s imagination, transporting them to “the open air of a heavenly Jerusalem as it were, where lizards crawl and flies buzz, all in a life of gold.”[x] The spatial narrative that is created by the Baldacchino’s imagery connects Rome to Jerusalem and thus the meaning as holy canopy to Bernini’s baldachin. Though the references were conceived from sculpture, meaning was derived from the architecture, which facilitates a spatial dimension to the work – one that causes the meaning to be revealed through the active experience of space rather than through a passive symbology.

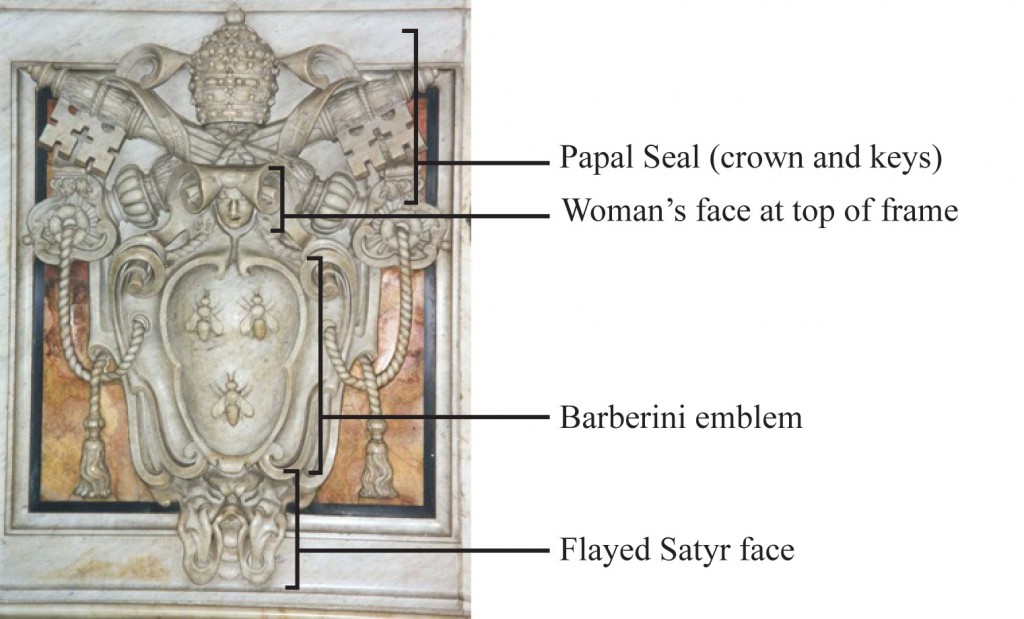

Bernini takes the performance of the Baldacchino a step further through his clever manipulation of the emblems that rest above the Tomb of St. Peter. While Renaissance masters before him saw history through an understanding of cosmic forms and proportions, Bernini pays close attention to the detailed imagery of ‘historical truth and decorum’, scrutinizing design for appropriate attire, expression, and views for his sculptural work.[xi] In architecture, design decorum was closely tied to the appropriate use of ‘emblems and armorial devices’, which not only held imagery, but also “signs and symbols which, as heraldry and emblematic art require, contain a certain element of secrecy.”[xii] Emblematic imagery gained another layer of meaning through its reference to political and social entities of the time; in the Baldacchino the emblem most used is the bee. Symbolic for Pope Urban VIII and the Barberini family the bees can be found flying amongst the laurel leaves and putti on the columns, resting on the drapery hung from the canopy, and used as ornament along the column bases. The bees cover the Baldacchino, but are most prominent as an emblem on the marble bases on which the twisting columns stand.

Here, contained in their proper places on a series of eight stemme (the representative shield), one each outward-facing side of the bases, the three bees rest as they’re seen on the Barberini coat of arms. It is amongst the stemma that Bernini is playful with his use of decorum and purposefully alters the appropriate to create a new allegory, hidden once again in the small details.

A deeper allegory, one of satire and social statement, is crafted into the Baldacchino through the stemme. Each stemma on the Baldacchino is composed of similar pieces. In the center lies the family crest, which is surrounded by a frame composed of the papal seal above the face of a woman (or in one case a cherub), and a flayed satyr’s head at the base (Fig 3).[xiii] At first glance, the eight stemme that surround the base of the canopy appear to be the same. Their similarities were close enough to go virtually unnoticed by the papal censors (or perhaps supported by the poetically aware pope), but concealed in the slightest changes of imagery lies a rich narrative on Bernini’s patron. The story varies from source to source, but the fable that developed about the stemma involved a difficult pregnancy. One tale of the stemme involves Urban’s favorite niece struggling with a difficult childbirth. The Pope was claimed to have prayed for her wellbeing and commissioned the Baldacchino in thanks.[xiv]

However, another tale, one supported by Sergei Eisenstein in Montage and Architecture, is of the Pope’s nephew, who impregnated a daughter of one of Bernini’s craftsmen and would not claim it as his own.[xv] Told of his friend’s dilemma, Bernini asked Urban VIII to convince his nephew to marry the young woman. A deeply moral man, Bernini was taken aback when the Pope refused and so the story goes that the stemme are a reminder of the Pope’s discarded legacy.[xvi] Both may perhaps be nothing more than allusion and myth developed over time, yet the capacity for the careful allegory should not be disregarded. The story emerges as one walks around the Baldacchino and may notice that the stemme change, most noticeably in the faces over the Barberini crest and the belly of the shield itself (Fig 4). A clockwise turn around the canopy reveals a building look of pain and hysteria in the woman’s face accompanied by a growing belly of the shield until the woman’s head being replaced by a smiling cherub resolves the narrative and the belly returns to its original slim posture.[xvii] Though many scholars dismiss the tales that have grown around this narrative as allusions, the comparison between the progression of the stemme and the process of childbirth is surprisingly clear.

Figure 4 - One of eight changing heads that top the stemma. Is it the Pope's niece or the stone mason's daughter? We may not know for certain, but the carefully placed detail creates a rich metaphor.

Bernini’s ability as a poet is evidenced in his ability to form metaphor from the otherwise static symbology of the stemme. The shield becomes a pregnant belly, the watching faces of increasing pain become a difficult pregnancy; even the flayed satyr face has been compared to the changing female ovaries of a pregnant woman. Bernini forges a narrative from these metaphors by stringing the stemme together into a narrative. The deeper meaning of the stemma remain concealed when separate, but create a new narrative when put together without corrupting each stemma’s ability to function as a basic emblem. Eisenstein compares Bernini’s use of narrative in the stemme to montage in cinema:

The answer to the riddle lies entirely in the full picture…In themselves, the pictures, the phases, the elements of the whole are innocent and indecipherable. The blow is struck only when the elements are juxtaposed into a sequential image.[xviii]

The ability of Bernini as poet to carefully form metaphor from the stemme has revealed a new conversation and thus has succeeded in activating the stemme as parts of the architectural performance of the Baldacchino, prompting visitors to engage in a ritualistic turn around the canopy in order to discover the narrative hidden within Bernini’s intricacies. What the stemme reveals is Bernini’s masterful ability to create meaning through the movement of the viewer around the Baldacchino and, if taking Eisenstein’s position, the potential for satire and social critique in architecture.

Approaching the Baldacchino in the present, these carefully laid layers of meaning become more difficult to decipher. Vivid imagery and sculpture are no longer the method for finding meaning and confronted with the abundant symbology and biblical reference of the Baroque, it becomes troublesome to understand what such objects as the Baldacchino mean. However, the basic poetics of Bernini’s work still attracts the modern visitor and even promotes a similar desire for discovery. The small intricacies of Bernini, like the pilgrim’s medallion or cheerful putti chasing bees, may not convey their symbolic meaning today, but they still manage to capture a visitor’s imagination. A fantastical world is opened up by Bernini’s work, a trait that seems lost in today’s architecture. Perhaps Bernini can still hold relevance to the contemporary architect through his ability to incorporate poetics into his architecture. Translated from sculptural imagery, the Baldacchino holds merit in Bernini’s use of details to express a narrative, an allegory, a fantastical series of metaphors that continue to incite imagination with or without the references they hold. As Marco Frascari introduces in The Tell-The-Tale Detail, “…architecture becomes the art of appropriate selection of details in the devising of a tale.”[xix] What is Bernini then, other than a skillful craftsman of tales, using the medium of his time to sculpt moving works into space? The media of the architect has radically changed from the Baroque, however, the potential for an architect to become a poet remains. Rediscovering the ability to craft allegory and narrative from space may allow the contemporary architect, as in the words of Fehl, “console, delight, and instruct all men.”[xx]

Christian Norberg-Schulz, Baroque Architecture (New York: Rizzoli Int. Press, 1979), 8. Norberg-Schulz sets the scene for the mindset of the Baroque age. Its important to understand where Bernini finds the source of his meaning and how his work was meant to be interpreted in the time that it was produced.

Christian Norberg-Schulz, Baroque Architecture (New York: Rizzoli Int. Press, 1979), 10.

Christian Norberg-Schulz, Baroque Architecture (New York: Rizzoli Int. Press, 1979), I0.

Philipp Fehl, “Hermeticism and Art: Emblem and Allegory in the Work of Bernini,” Artibus et Historiae 7, no. 14 (1986) 153. In his essay on Allegory, Philipp Fehl introduces Hermeticism as a way of understanding the revealing process of Baroque art.

Philipp Fehl, “Hermeticism and Art: Emblem and Allegory in the Work of Bernini,” Artibus et Historiae 7, no. 14 (1986) 153.

Christian Norberg-Schulz, Baroque Architecture (New York: Rizzoli Int. Press, 1979), 69. Norberg-Schulz mention’s Bernini’s use of decoration periodically through his chapter on Churches, but often in contrast to Borromini’s use of geometry. Wittkower fleshes out a better picture of Bernini’s use of sculpture in architecture in the following reference.

Rudolf Wittkower, Art and Architecture in Italy 1600-1750 (London: Yale Univ. Press, 1999), 169.

Rudolf Wittkower, Art and Architecture in Italy 1600-1750 (London: Yale Univ. Press, 1999), 175. Wittkower goes into further depth about the columns of the Baldacchino and their effect. Fehl also briefly discusses the imagery of the twisting columns on page 176 of his piece on Allegory.

Philipp Fehl, “Hermeticism and Art: Emblem and Allegory in the Work of Bernini,” Artibus et Historiae 7, no. 14 (1986) 176-177. Fehl mentions here that Bernini even managed to cast the real objects into the molds to capture their true likeness. How he managed to cast a lizard and a fly are stunning examples of his search for life in sculpture.

Philipp Fehl, “Hermeticism and Art: Emblem and Allegory in the Work of Bernini,” Artibus et Historiae 7, no. 14 (1986) 176.

Rudolf Wittkower, Art and Architecture in Italy 1600-1750 (London: Yale Univ. Press, 1999), 171. Wittkower discuss briefly how particular Bernini was to be as true to history and proper imagery for what he wanted to convey. Nobility needed to look noble and thus sculpture of nobility held a specific decorum that Bernini strove to follow.

Philipp Fehl, “Hermeticism and Art: Emblem and Allegory in the Work of Bernini,” Artibus et Historiae 7, no. 14 (1986) 156. The symbolism of the family emblems of the time held great social importance, as they showed ownership and represented the families from which they originated.

Philipp Fehl, “The ‘Stemme’ on Bernini’s Baldacchino in St Peter’s: a Forgotten Compliment,” The Burlington Magazine 118, no. 8 (Jul., 1976): 487

Philipp Fehl, “The ‘Stemme’ on Bernini’s Baldacchino in St Peter’s: a Forgotten Compliment,” The Burlington Magazine 118, no. 8 (Jul., 1976): 488. Though he presents this tale, Fehl argues for another view that the birth of the cherub is alluding to the Barberini Pope bringing peace into the world through struggle.

Sergei M. Eisenstien, “Montage and Architecture,” Assemblage 10 (Dec. 1989), 122. Eisenstien pursues his preferred story, but through the hypothesis of many other scholars. He mentions the mixed opinions on the tale of the stemme throughout his discussion of the Baldacchino.

Sergei M. Eisenstien, “Montage and Architecture,” Assemblage 10 (Dec. 1989), 125.

Philipp Fehl, “The ‘Stemme’ on Bernini’s Baldacchino in St Peter’s: a Forgotten Compliment,” The Burlington Magazine 118, no. 8 (Jul., 1976): 487-491. Sergei M. Eisenstien, “Montage and Architecture,” Assemblage 10 (Dec. 1989), 122-126. Both authors present excellent accounts of the procession around the Baldacchino, although each start on different side, slightly changing the narrative. However, each interpretation supports the tale they tell.

Sergei M. Eisenstien, “Montage and Architecture,” Assemblage 10 (Dec. 1989), 128.

Marco Frascari, “The Tell-The-Tale Detail,” Via 7 (1984), 26. Frascari connects the past with the present through his look at details the first half of his essay. He leads the discussion to the work of Carlo Scarpa, where he goes in depth as to the architect’s use of the detail to create narrative. Perhaps and interesting comparison could be made between Bernini and Scarpa and their use of poetical space.

Philipp Fehl, “Hermeticism and Art: Emblem and Allegory in the Work of Bernini,” Artibus et Historiae 7, no. 14 (1986) 153.

[xxi] J.B. Ward Perkins, “The Shrine of St. Peter and Its Twelve Spiral Columns,” The Journal of Roman Studies 42 (1952), 21-33.